There is an “unconventional” index that economists and investors use to predict economic downturns.

It’s called the Skyscraper Index. Invented by Andrew Lawrence, a property analyst at Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein, the index was based on a relatively simple idea – that the completion of the world’s tallest building is inevitably a marker for the start of the next global economic crisis.

Think about that for a second.

The world’s tallest skyscraper is the Burj Khalifa in Dubai. It stands at 829.8 metres high. That’s roughly 2.62 times the size of Melbourne’s tallest building, Australia 108 (316.7m). The Burj Khalifa officially opened in Dubai just weeks after the Emirate’s debt crisis began. But this anomaly, appears to be quite common.

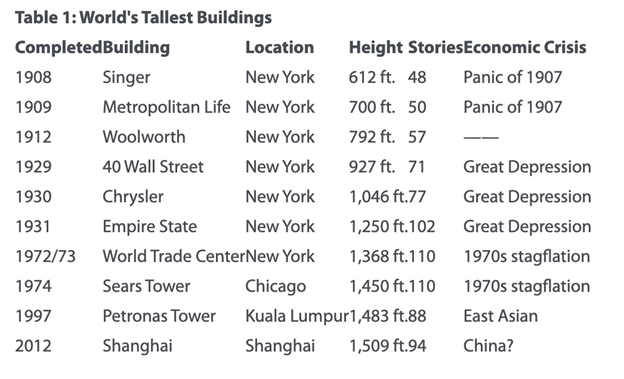

The Skyscraper Index is considered to be one of the most robust bubble indicators over long periods. The index specifically involves the world’s tallest skyscraper, whose construction progress matches up with many historical financial crises. The two variables are tabulated below.

Another string of tall towers — 40 Wall Street, the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building — began rising from street-level Manhattan shortly before the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

The next record-holders were the World Trade Center towers and the Sears Tower, opened in 1973 during the 1973-74 stock market crash and the 1973 oil crisis. The last example Lawrence was able to use in 1999 was the Petronas Twin Towers, opened in the wake of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis; it held the world height record for five years.

Taipei 101, 449 meters high, was completed in 2004, after the Dot-com Bubble of 2000-03.

The Burj Khalifa, 828 meters high, opened in 2008 in the middle of the Great Recession of 2007-09.

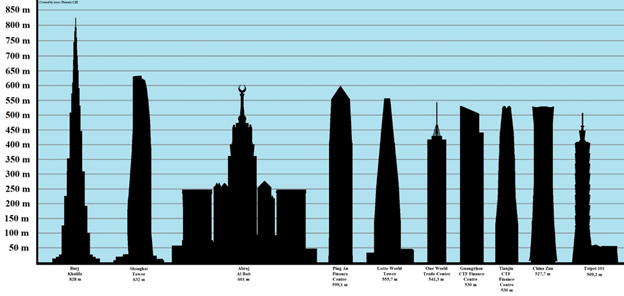

As of 2020, the tallest skyscrapers in the world are #1 Burj Khalifa in Dubai; #2 Shanghai Tower, which at 632m is the tallest twisted building; #3 Abraj Ai Bait Clock Tower in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the highest building with a clock face; #4 Ping An International Finance Centre in Shenzhen, China; and #5 Lotte World Tower in Seoul, South Korea.

Just missing the top five is One World Trade Center in New York, built to replace the Twin Towers. Completed in 2014 at 554.5m (1,819 feet), the landmark and 9/11 Memorial is the tallest building in the Western hemisphere.

For the next 71 tallest buildings, visit the Wikipedia page, or check the table with a shorter list below.

An obvious question: how reliable is the Skyscraper Index? Intuitively it seems wrong. The skyscraper is a symbol of economic and financial success, the pinnacle of a country’s capitalistic ascent. How can building the world’s tallest building cause an economic collapse? Surely these are periods of great hope and prosperity.

Well that is precisely the point.

Lawrence reportedly linked the phenomenon to overinvestment, speculation and monetary expansion.

The simple concept also fits within the framework of the Austrian Business Cycle Theory. The latter borrowed from the 18th century theories of Richard Cantillon, an Irish-French economist. Mark Thornton, an American economist with the Austrian School, in 2005 laid out three “Cantillon effects” which validate the Skyscraper Index. First, a decline in interest rates at the onset of the boom drives land prices. Second, a decline in interest rates allows an average-sized firm to increase, creating demand for office spaces. Third, low interest rates provide investment to construction technologies that enable developers to break earlier height records. All three effects are said to peak at the end of the expansionary period.

A 1995 analysis of New York and Chicago’s experience by Carol Willis, the founder, director and curator of the Skyscraper Museum in Manhattan, found that “the tallest buildings generally appear before the end of a boom, their height driven up by the speculative fever that affects both developers and lenders.” The architectural historian cites cyclically inflated land values as the principal factor for increases in building height.

The Burj Khalifa is a good example of a skyscraper built during a housing bubble. In October 2009, construction company Emaar announced it had completed the building’s exterior. Within two months, the Dubai government nearly defaulted on its loans.

“For all the ambition of its construction, Dubai’s new Khalifa Tower is a frightening, purposeless monument to the subprime era,” The Daily Telegraph commented at the time.

In a 2011 article, Forbes muses over reasons the Skyscraper Index is consistently useful. The passage is worth quoting in full, since it appears to echo what Carol Willis’ analysis found:

Skyscrapers are inherently speculative ventures, in that they are rarely, if ever, built by their intended occupants or with committed tenants. “Build it and they will come” captures the prevailing spirit. Thus you can think of the world’s tallest skyscrapers as indicators of lofty overconfidence.

Second, because speculators rarely build such structures with their own money, skyscrapers are powerful evidence of “easy money.” Accepting the importance of these two variables in creating a fertile context for bubble formation, skyscrapers are actually a spectacular indicator of bubbly conditions. The economist Mark Thorton eloquently summarized the context surrounding the construction of the world’s tallest skyscrapers: “First, a period of easy money leads to a rapid expansion of the economy and a boom in the stock market… credit fuels a substantial increase in capital expenditures … [and] this is when the world’s tallest buildings are begun.”

Although critics have dismissed the Skyscraper Index as an unreliable tool — the post-World War I recession, the recession of 1937 and the early 1980s recession were not marked by any record-breaking projects — the current skyscraper building boom would appear to foreshadow darker economic times ahead.

Returning to the table above, notice that, of the 41 tallest skyscrapers, 11 built within the past five years are in China, compared to three in the United States. Of the 43 highest buildings under construction, 32 are in China, or 74%.

Evergrande crisis

Is it a coincidence that China’s skyscraper building boom is occurring at the same time as the Evergrande crisis that has been dominating financial headlines? We think not.

As we reported in our last article, the Evergrande Group grew to be one of China’s largest companies by borrowing more than $300 billion. It currently owns over 1,300 projects in nearly 300 cities across China, and has diversified its business beyond real estate to include wealth management, electric cars, and food & drink manufacturing. Evergrande even owns one of the country’s biggest football (soccer) teams, Guangzhou FC.

Last year, Beijing brought in new rules to control the amount owed by big real estate developers. The new measures led Evergrande to sell some of its properties at deep discounts to ensure there was enough cash flow, but the firm is now struggling to meet the interest payments on its debts.

The uncertainty has seen Evergrande’s stock price plummet by around 85% over the past year, and its corporate bonds have been downgraded by global credit rating agencies.

It’s estimated around 1.5 million people could lose the deposits on their homes if Evergrande goes under. Then there are the companies that Evergrande does business with, like construction and design firms. They could potentially go bust if their deposits aren’t repaid. The effect on the country’s financial system could also be far-reaching; Evergrande reportedly owes money to around 171 domestic banks and 121 other financial firms.

The banks have been told they won’t receive interest payments on loans due Monday, Sept. 20. Evergrande will be tested again this Thursday, Sept. 23, when $84 million in interest payments on its bonds are due. Sept. 29 is the deadline for another $45.5M in interest on March 2024 notes. The bonds would default if Evergrande fails to pay the interest within 30 days.

In the meantime, Evergrande has started repaying investors in its wealth management business with real estate. Market participants are bracing for what could be one of China’s largest-ever debt restructurings. According to Reuters, regulators have warned that its $305 billion of liabilities could spark broader risks to China’s financial system if its debts are not stabilised.

If Evergrande defaults, banks and other lenders may be forced to lend less, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) told the BBC, which could lead to a credit crunch whereby companies struggle to borrow at affordable rates.

Is the Chinese housing market susceptible to a bust? You bet. In 2011, extremely easy monetary conditions and negative real interest rates encouraged many investments that wouldn’t normally be economic. Dozens of “ghost cities” meant for millions were built, that remain under or un-populated.

In 2013 China suffered a mini-crash, when its post-2008 stimulus came to an end and consumption fell by 10% over the next two years. As stated by the Washington Post,

That glimpse into the abyss, and the credit-fueled construction splurge unleashed to prop up economic growth afterward, is one factor in the problems being faced now by Evergrande.

The main worry in China is the property bubble that has been building for the past two decades. As millions of farm workers flocked to the cities at the dawn of the 21st century, real estate speculation became a national pastime. The end result has been the same as in many countries, including Canada, ie., high rents, unaffordable housing and younger generations angry at being locked out of the real estate market.

In 2017, President Xi Jinping stated that “housing is for living in, not for speculation.” The government’s recent Three Red Lines policy for property developers was aimed at reducing debt, curbing runaway prices and lifting construction standards.

That brings us to the “Evergrande Moment”.

Investors world-wide are concerned that Evergrande’s unraveling could affect the Chinese property sector and the commodities that feed it, such as iron ore, steel and copper.

First off, we don’t believe Evergrande is another Lehman Brothers. A deal will be done to stabilize Evergrande’s debt and restructure bonds and loans by selling most of its assets; some investors will be repaid with real estate.

Second, while there is certainly the risk of commodity prices coming off the boil — China consumes half the world’s steel and its property sector accounts for about 20% of global demand — a look at previous property bubble bursts shows a muted reaction. When Japan’s housing market went bust in 1991, its steel output fell by only 20%. South Korea’s steel production did drop by a third in 1997, the year of the Asian financial crisis, but it recovered quickly, the following year.

WaPo notes that, for all the government’s promises of [steel] output curbs, usage as of July this year was running nearly 10% higher still.

Conclusion

The influential newspaper believes the health of the Chinese steel industry is good reason to think the markets are over-reacting to Evergrande. I agree. Take a look at rebar.

The price of the reinforcement bar used on construction sites is at almost the same elevated level it was two months ago, before its key ingredient — iron ore — starting falling and Monday drifted below $100 a tonne for the first time in over a year.

That suggests that end-use demand is still pretty much where it was before this panic started, which should deliver mill owners handsome profits, WaPo states, before concluding that, we’ve not yet seen the reckoning with its steel addiction that China, and the world, ultimately needs. Until that happens, don’t assume this market is dead.

Steel demand is fueled by property and infrastructure, and skyscrapers are among the most steel-intensive structures ever built. As mining investors we need to watch closely what happens with China’s skyscraper building spree — remember three-quarters of these new tall towers are being built in China, and the Chinese construction industry consumes a lot of iron ore for steel, along with copper and other raw materials — but we also need to keep the demand drivers in perspective.

BloombergNEF came out with a report this week, stating that the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy could require as much as $173 trillion in energy supply and infrastructure investment over the next three decades. Energy metals like lithium, nickel and cobalt, and industrial metals such as copper and steel, are driving the next commodities supercycle.

As we have noted previously, it takes several years to develop a mine from discovery to production, in some jurisdictions it’s 20 years, so the time to invest in new mineral deposits is now.

Keeping ahead of demand will ensure that enough construction raw materials are available to see China through its skyscraper building boom, keeping commodity prices within reach and helping to prevent the housing bubble from popping.

And so, if the skyscraper effect is true, that could be good news for using it as a market timing signal for the world economy.

Article courtesy of AheadoftheHeard